Yes, I admit it: I have IKEA furniture. While my design degree has given me a deep appreciation for high-quality, midcentury furnishings, my budget hasn't quite caught up to my taste, and I'm left sheepishly amassing an array of tiny IKEA Allen wrenches in a junk drawer. Maybe that's why I was excited to see Greycork's Indiegogo campaign. The furniture startup hopes to take a bite out of IKEA's market, luring consumers with higher quality goods at a similar price point. At the cornerstone of its recently launched collection (available for pre-order only through the campaign) is a sofa, which Greycork promises can be assembled in four minutes, no tools (not even Allen wrenches) required.

![]()

Spurred by the founder's own frustrating experience assembling and disassembling furniture over the course of several moves, Greycork was established in June 2013 by John Humphrey. "I thought there could be an opportunity to create something better looking that I could have a stronger connection to," he says. With a background in manufacturing, Humphrey had spent time working on assembly lines at the age of eleven for his family's lumber business, which dates back to the 1880s. In 2014, the Rhode Island native invited Bruce Kim, a RISD alumnus, to join him as a co-founder—and the team grew from there, as they brought on two more RISD alumni, Alec Babala and Jonah Willcox-Healey.

After a few missteps with their initial product line, a series of tables, the team took a step back. "We went too fast, too soon," Babala says. "We changed course to focus on human-centered design, IDEO, and their three phases: inspiration, ideation, implementation." Last January, the team sat down with a design kit from IDEO, and began a series of interviews with users that continued until late March. "After that first round, we decided to go deeper with it," Babala says. "This time, we started to do more personal interviews. I think between the four of us we got about a hundred one-on-one interviews about what makes a personal space, what makes a social space, what makes a productive space." The interviews led the team to focus on the living room as the central part of the home, and the sofa as its most crucial element. "So, that's where we started," Humphrey says.

The team employed another set of criteria, a decision-making matrix, to help them hone in on their idea and make critical decisions around their product offering. "Our decision-making matrix was: transportability, affordability, aesthetically appealing, ship-ability, durability," Babala says. After understanding their users' needs, as well as the price-point they were willing to meet, the team looked at options for manufacturing—adding a new layer of constraints.

![]()

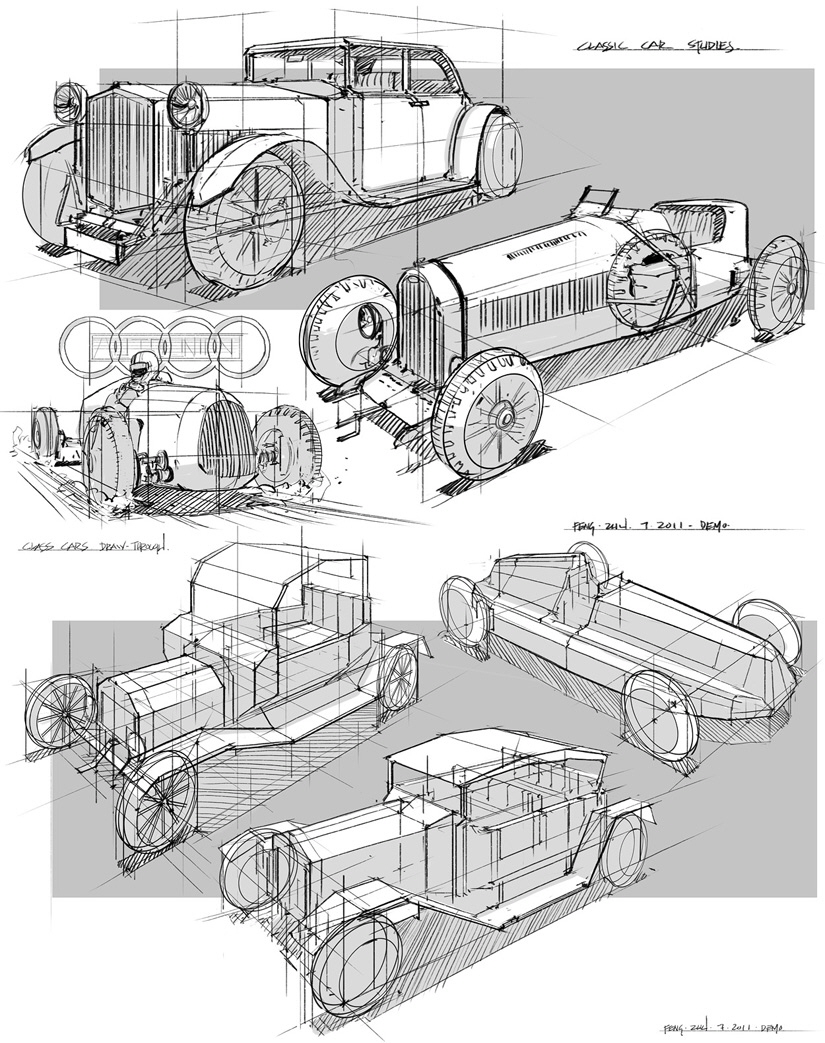

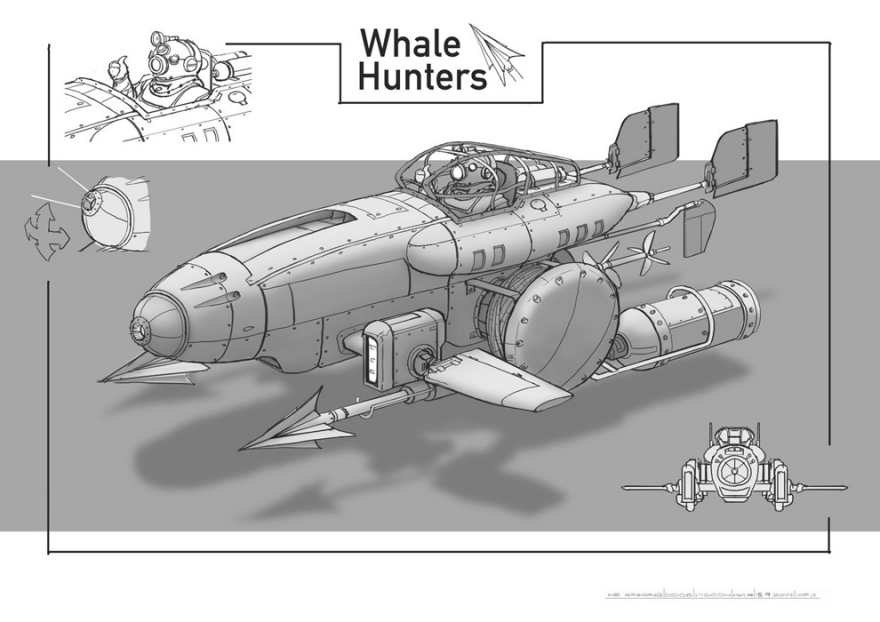

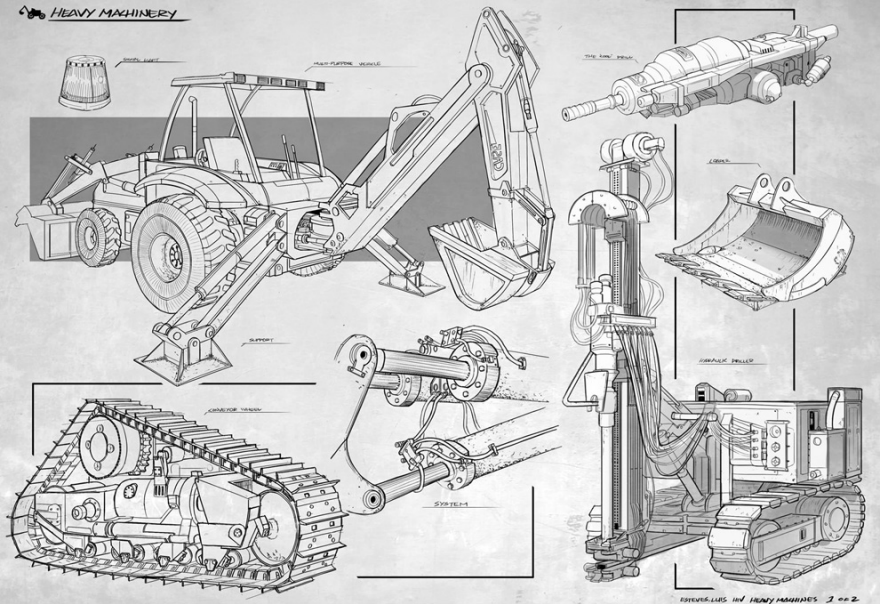

"Starting with materials, we knew we could use ash, MDF and thin-plated steel because they're relatively cheap," Kim says. "And also we limited ourselves to working with these two partners—Panel Processing, which is the biggest panel fabricator in North America, and Waddell Manufacturing, who primarily do wooden components that involve turning." Limited by panel-and-dowel construction, the designers began sketching, looking to Japanese aesthetics as a source of inspiration. "[Japanese design] uses really, really simple geometries and forms that work with our constraints," Kim says.

![]() Sofa sketches

Sofa sketchesAnother limitation was the material sizing itself. Stock paneling comes in two sizes, 4-by-8 and 5-by-8 feet, so the designers had to work within those dimensions to use material efficiently. "If our seat panels were an inch thicker or an inch wider, we would have only been able to get one piece out of a whole sheet of 4-by-8 [feet]," Kim says. "Every single component on the sofa has been designed to get better yield from stock materials." Any leftover material was repurposed for another component in the collection.

Kim and Willcox-Healey did numerous sketches—roughly 30 iterations—of how components could go together before moving their designs into CAD. On the computer, the designers were able to see how the couch looked from all angles. The team used the decision-making matrix to narrow down their choice to two or three designs, and then started full-scale prototyping in-house using lathes and small-scale machinery. Knowing its manufacturer's capabilities, Greycork tailored the designs to Waddell's equipment, leaning on them to produce as many similar components as possible. As a result, the sofa features six dowels along its back, six legs and a rail, which all screw into a standard panel base produced by Panel Processing.

Shipping and handling posed yet another challenge to the small team, who had to scale their design to keep it within budget and under freight rules. All shipping through UPS and FedEx is calculated by dimensional weight, a system put in place to avoid shipping any excess air and to have a better box-to-internal-item ratio. Calculated by multiplying length by width by height and dividing by 166, that dimensional weight is then combined with another formula for larger packages (like Greycork's sofa). Length and girth are added together, doubled and that resulting number has to be greater than 130 to make the minimum billing weight 90 pounds. "This second equation makes it difficult to have a large box since you can be charged for something that weighs more than it really is... thus it's more expensive to ship," Willcox-Healey explains.

The other tricky part of shipping large boxes involves standard shipping versus freight shipping. If the number from the second equation exceeds 165 inches, then the package has to be charged for freight shipping—moving it to a whole other price zone. "Keeping our packaging size under 165 has really been our biggest restriction," Willcox-Healey says. And right now they are just under that magic number—77 plus 5 doubled equals 164. "We're exactly a half-inch away from our shipping costs jumping three times," Kim says. The team employed several techniques to keep the sofa within the necessary dimensions, including getting the seat frame as thin as possible and using compression foam for the seat cushions.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The magic number for the seat frame itself ended up being three-fourths of an inch, a number derived from "having a bunch of people jump on it," as well as some slightly more scientific tests of frame warpage. "We put a panel vertical to the seat frame, and we put load onto the panel, and marked how much it deflected," Kim says.

As for the seat cushion, the team was quickly educated on the ins and outs of compression foam, learning how to compress them properly, what kind of foam to use to make sure that it would rebound later, as well as how to order and source the material. Greycork worked with an overseas manufacturer to get the best amount of yield from one bun, a stock foam standard that comes in 12-inch cubes. "We had to get the whole package down to five inches of height, leaving one inch for the upholstered cushions," Kim says. "We couldn't be over six inches of foam, or it wouldn't compress down and we would have to ship freight."

![]()

The Greycork team used the same machine used by foam mattress companies like Casper to compress the foam down for shipping. "Basically, we're using the same process of putting it in a bag, sealing it, and then when it's opened by consumers it expands to the full form," Willcox-Healey says. "With that, you have to use a very high-quality foam. If you use a low-quality foam, it will stay at 60 percent of its compressed form, like a pancake." The same process was used for the pillows, which were compressed down to three-fourths of an inch, stuffed into machine-washable foam slipcovers and sealed in bags for shipping.

The foam itself has multiple layers, including a plush polyester fiber, two inches of soft foam and three inches of firm foam. That layering of various densities was another lesson learned by the Greycork team, who had very little experience with soft goods and upholstery prior to this project. "When you sit on something, you don't always understand that there can be three different or four different types inside so that you have that soft-but-firm feeling," Willcox-Healey says. "Visually, you're using something that just looks like a square piece of foam, but that can actually be very harsh to sit on. What can you do to a piece of fabric in how you stitch it together or how tight it is to look more presentable to a consumer?" Aside from the foam and upholstery, all other manufacturing for the sofa was completed in the U.S.

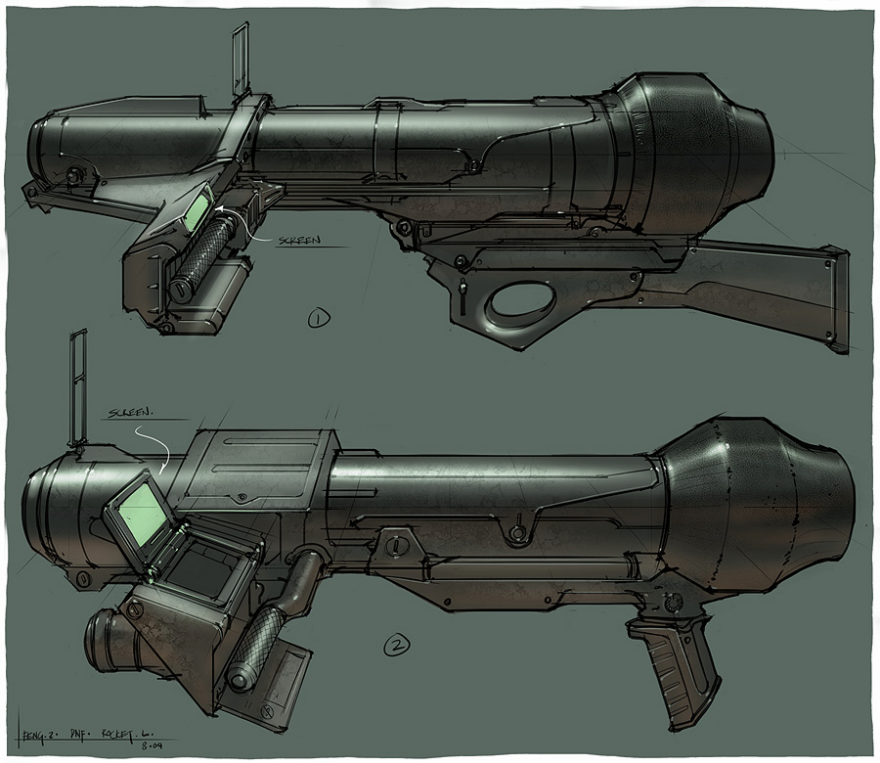

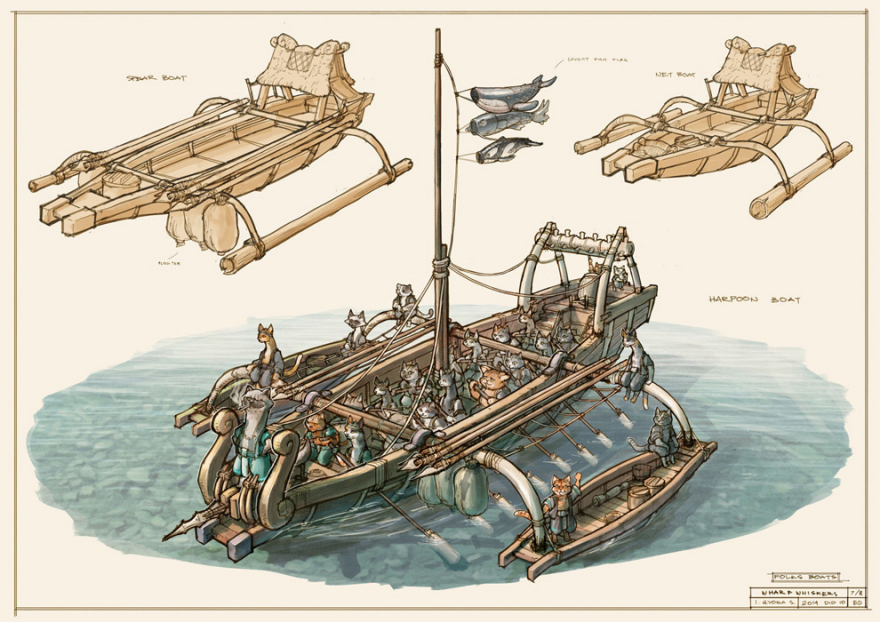

![]() The Greycork team on their sofa and chaise

The Greycork team on their sofa and chaiseWhen that perfectly sized 78-by-35-by-5 inch box from Greycork first arrives, a user will lay it on the ground, snip the force wraps and open it up. Laying on top is a poster with an orthographic view of the sofa and, on the back, instructions for assembly. "You can either choose to assemble it like a baller with the poster, or flip it over to use the instructions," Willcox-Healey says. Inside the box are three flat-back pillows, a back rail, a frame, six legs, six washers and six thumbscrews. After attaching the back rail to the base frame using the thumbscrews, the legs are bolted into the base and cushions are fluffed back out to full size. "No tools required," Babala says.

The Greycork sofa will eventually retail for $650, but it's currently available for $450 through the Indiegogo campaign (with free shipping in the U.S.)—a price that is indeed very competitive with IKEA sofas, and finally gives lean-budget design lovers like me a viable new furnishing option.

![]()