This is the seventh of our ten Tech Specsinterviews. Previously, we talked to Ram Trucks' Greg Howell.

Name: Andrew Kim

Job title: Designer at Microsoft, and design blogger at Minimally Minimal

Background: I went to Art Center College of Design, did a couple of internships and worked at places like Google and Frog Design, and then started my first full-time job here at Microsoft about two years ago. For most of my first year, I worked purely on Xbox projects. Now I’m working on general Microsoft projects, including Windows 10.

Computer setup: I have two computers on my desk. One is a Surface Pro 3 running Windows. That’s the workstation I use for rendering in programs like Keyshot and SolidWorks, and I also use it for general corporate stuff like getting on the internal network. And then for the graphics work I do, I have a 15-inch MacBook Pro that I use for most of the Adobe programs, like Illustrator and InDesign.

I have a 30-inch cinema display that I use for whichever computer I’m working on. And then when I really need some extra horsepower for CAD, I also have an HP all-in-one workstation that I’ll use occasionally. It used to be on my desk but now it’s elsewhere in the studio. For most everyday jobs, the Surface is good enough for my needs.

How much of your workday do you spend in front of the computer? Basically whenever I’m not in meetings, so that’s about 75 percent of the day.

Andrew Kim

Andrew KimMost used software: Illustrator would be number one, followed by InDesign, Photoshop, Keyshot and, lastly, SolidWorks. That’s pretty much it for creative tools, but then of course you have other productivity software—PowerPoint for presentations and Outlook for communication.

Software that you thought you’d use more often than you do: Apps like Evernote. When I graduated, I liked the idea of having a digital scrapbook or mental diary, so I started using Evernote. But my use just tapered off, and I reverted back to using a physical sketchbook and having random piles of things that I collect in different locations—whether it’s on Pinterest or bookmarking links or dragging images onto my desktop.

Phone: iPhone 6

Favorite apps: I’m completely addicted to Instagram right now, so that would be number one. VSCO is a brilliant photo-editing app; I love the way it works. That’s possibly the app I use the most. Along with that, there’s an app called SKWRT. It’s a perspective tool for photo editing that I also really like.

Other than that, I just use stock apps—Mail, iMessage. Of course, being in Seattle, I use Dark Sky a lot, because you never know when it’s going to rain and you have to be ready at all times.

Apps that are actually useful for your work: As mundane as it sounds, I think the camera app and the photo app. A lot of times instead of taking notes, I will just take a photo of something. That’s actually something I use all the time at work, whether it’s taking a picture of notes on a whiteboard or a material sample that I want to reference later.

Other devices: Not any that come into my workflow. There was a period when I wanted to move all of my sketches over to digital. I have an iPad, so I tried using Paper, and I’ve also considered using Surface Pro to do sketches on—but I’ve come back to just doing sketches in a notebook.

Other machinery/tools in your workspace: We definitely utilize 3D printers and CNC machines, but those are not directly in my workspace. We’re sending files off to the model shop and they prepare them for the following day. Otherwise, we do have a couple of MakerBots around the studio, but I haven’t utilized them yet.

Kim's desk at Microsoft

Kim's desk at MicrosoftTools or software you’re thinking of purchasing: I’ve actually thought about learning Rhino, just on a personal level. We have quite a few Rhino users in the studio, and being someone who’s purely about SolidWorks, I always get jealous when they’re able to create sketches of 3D models at an incredible speed.

How has new technology changed your job in the last 5–10 years? I’ve only been at this job for a couple years, and I don’t think there’s been a massive shift in that time. One big difference between being in school and being at Microsoft, however, is that at Microsoft you’re able to print anything you want—money isn’t a boundary like it is when you’re a student. So just on a personal level of making models or developing ideas, there’s definitely a level of freedom here that you don’t get in school.

In his first year at Microsoft, Kim worked exclusively on Xbox projects.

In his first year at Microsoft, Kim worked exclusively on Xbox projects. Now Kim is working on general Microsoft projects, including Windows 10—which will feature holographic computing.

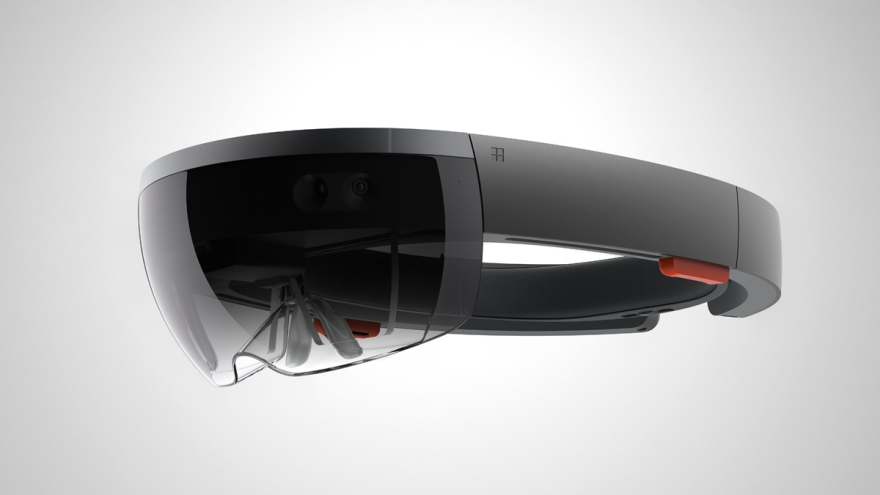

Now Kim is working on general Microsoft projects, including Windows 10—which will feature holographic computing. Microsoft's HoloLens

Microsoft's HoloLensWhen it comes to new tech, are you a Luddite, an early adopter or somewhere in between? Somewhere in between. I like to try out new tech, but I’m also someone that doesn’t like to mess with a lot of things. I like to have things that work, and have a workflow that works the way I like it. But I am always fascinated by new technology.

Do you outsource any of your tech tasks? Yes, especially when it comes to model making—a lot of that is outsourced. We have a couple of model shops that we use all the time, because our shop doesn’t have the ability to do things like VM or machining at a more delicate scale.

What are your biggest tech gripes? I think right now it would be that I still can’t have a digital notebook and have it feel as intuitive as a physical one. That’s an idea I’ve always liked, hence my experiments with things like Evernote, Sketchbook Pro and Surface. But I think we’re still a ways away. Even an app like Paper—there’s still that difficulty of getting out the tablet, turning it on, going into the app, opening your notebook, creating a new page. It’s not the same as just opening your sketchbook and putting down an idea. So for now I’m still 100-percent sketching on paper.

I think the root of my dissatisfaction with software right now is the lack of immediacy. We’ve grown immensely in terms of speed and performance, but it’s still not the same as paper.

What do you wish software could do that it can’t now? I think the root of my dissatisfaction with software right now is the lack of immediacy. We’ve grown immensely in terms of speed and performance, but as I mentioned before, it’s still not the same as paper. There’s still something so raw and tactile about paper that I miss when I do anything in software. Even the difference between cutting things out and gluing them down on paper versus using Illustrator—I think once we can get that level of tactility in software it will be really incredible.

Finally, we've all had instances of software crashing at the worst possible moment, or experienced similar stomach-churning tech malfunctions. Can you tell us about your most memorable tech-related disaster? The biggest tech trauma that I’ve had was when I was a student and I was on vacation in Korea. It was the first time that I had a laptop hard drive fail, and I lost all of my data. I was so stupid back then—I didn’t even have a backup, so I lost all my music, all my photos, everything. I ended up having to scavenge through different external drives and thumb drives, looking for anything that I could save. That was the worst tech experience for me, personally. The only positive aspect was that I had to start again with a new computer, and it was like having a blank canvas—it was sort of refreshing to have this completely new start. But now, of course, I religiously back up everything in two locations.